Libya Calls Cease-Fire After Britain and France Vow Action

‘Soon’

‘Soon’

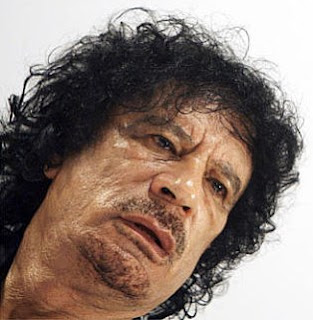

Hours after the United Nations Security Council voted to

authorize military action and a no-fly zone, Libya executed a remarkable

about-face on Friday, saying it would call an “immediate cease-fire and the

stoppage of all military operations” against rebels seeking the ouster of Col.

Muammar el-Qaddafi.

authorize military action and a no-fly zone, Libya executed a remarkable

about-face on Friday, saying it would call an “immediate cease-fire and the

stoppage of all military operations” against rebels seeking the ouster of Col.

Muammar el-Qaddafi.

The announcement came from Foreign Minister Moussa Koussa

after Western powers said they were preparing imminent airstrikes to prevent

Libyan forces from launching a threatened final assault on the rebels’ eastern

stronghold in Benghazi.

after Western powers said they were preparing imminent airstrikes to prevent

Libyan forces from launching a threatened final assault on the rebels’ eastern

stronghold in Benghazi.

It was unclear what effect a cease-fire, if honoured, might

have, but the offer drew some scepticism in the West. Prime Minister David

Cameron told the BBC of Colonel Qaddafi: “We will judge him by his actions, not

his words.”

have, but the offer drew some scepticism in the West. Prime Minister David

Cameron told the BBC of Colonel Qaddafi: “We will judge him by his actions, not

his words.”

Mr Cameron told the House of Commons that the British Air

Force would deploy Tornado jets and Eurofighter Typhoon warplanes, “as well as

air-to-air refuelling and surveillance aircraft.”

Force would deploy Tornado jets and Eurofighter Typhoon warplanes, “as well as

air-to-air refuelling and surveillance aircraft.”

“Preparations to deploy these have already started, and in

the coming hours they will move to airbases from where they can take the

necessary action," Mr Cameron said.

the coming hours they will move to airbases from where they can take the

necessary action," Mr Cameron said.

France reacted cautiously to the Libyan announcement.

Colonel Qaddafi “begins to be afraid, but on the ground, the threat hasn’t

changed,” the French foreign ministry spokesman, Bernard Valero, said Friday.

“We have to be very cautious.”

Colonel Qaddafi “begins to be afraid, but on the ground, the threat hasn’t

changed,” the French foreign ministry spokesman, Bernard Valero, said Friday.

“We have to be very cautious.”

Earlier, François Baroin, a French government spokesman,

told RTL radio that airstrikes would come “rapidly,” perhaps within hours,

after the United Nations resolution late Thursday authorized “all necessary

measures” to impose a no-fly zone.

told RTL radio that airstrikes would come “rapidly,” perhaps within hours,

after the United Nations resolution late Thursday authorized “all necessary

measures” to impose a no-fly zone.

But he insisted the military action was “not an occupation

of Libyan territory.”

of Libyan territory.”

Rather, it was designed to protect the Libyan people and

“allow them to go all the way in their drive, which means bringing down the

Qaddafi regime.”

“allow them to go all the way in their drive, which means bringing down the

Qaddafi regime.”

Other French officials said that Mr Baroin was speaking to

heighten the warning to Colonel Qaddafi, and that in fact any military action

was not that imminent, but was still being coordinated with allies like Britain

and the United States.

heighten the warning to Colonel Qaddafi, and that in fact any military action

was not that imminent, but was still being coordinated with allies like Britain

and the United States.

President Nicolas Sarkozy of France and Mr Cameron will

attend a meeting in Paris on Saturday with European, European Union, African

Union and Arab League officials to discuss Libya, the Elysee announced.

Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon of the United Nations will also participate, his

office said.

attend a meeting in Paris on Saturday with European, European Union, African

Union and Arab League officials to discuss Libya, the Elysee announced.

Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon of the United Nations will also participate, his

office said.

Apparently pulling back from the increasingly bellicose

statements as recently as Thursday from Colonel Qaddafi and his son Seif

al-Islam, Mr Koussa — his hands shaking as he read a statement at a news

conference Friday afternoon — said that the Qaddafi government would comply

with the United Nations resolution by halting combat operations.

statements as recently as Thursday from Colonel Qaddafi and his son Seif

al-Islam, Mr Koussa — his hands shaking as he read a statement at a news

conference Friday afternoon — said that the Qaddafi government would comply

with the United Nations resolution by halting combat operations.

“Libya has decided an immediate cease-fire and the stoppage

of all military operations,” Mr Koussa said. He did not take questions.

of all military operations,” Mr Koussa said. He did not take questions.

It was not immediately possible to confirm that military

action had ceased either on the eastern front or around the besieged rebel-held

city of Misurata in the west. Mr Koussa did not say whether the Libyan

government intended to restore water, electricity and telecommunications to

Misurata.

action had ceased either on the eastern front or around the besieged rebel-held

city of Misurata in the west. Mr Koussa did not say whether the Libyan

government intended to restore water, electricity and telecommunications to

Misurata.

Mr Koussa said he expressed “our sadness” that the

imposition of a no-fly zone would also stop commercial and civilian aircraft,

saying such measures “will have a negative impact on the general life of the

Libyan people.”

imposition of a no-fly zone would also stop commercial and civilian aircraft,

saying such measures “will have a negative impact on the general life of the

Libyan people.”

And he called it “strange and unreasonable” that the

resolution authorized the use of force against the Qaddafi government, “and

there are signs that this may indeed take place.” Mr Koussa called the

resolution a violation of Libyan sovereignty as well as of the United Nations

charter, and repeated a call for a “fact-finding mission” to evaluate the

situation on the ground.

resolution authorized the use of force against the Qaddafi government, “and

there are signs that this may indeed take place.” Mr Koussa called the

resolution a violation of Libyan sovereignty as well as of the United Nations

charter, and repeated a call for a “fact-finding mission” to evaluate the

situation on the ground.

Shortly before Mr Koussa spoke in Tripoli, Mr Cameron told

Parliament in London that Britain, a leading backer of the no-fly resolution,

had begun the preparations to deploy Tornado and Typhoon warplanes along with

aerial refuelling and surveillance aircraft. He said the planes would move “in

the coming hours” to bases where they could start implementing the no-fly zone.

Parliament in London that Britain, a leading backer of the no-fly resolution,

had begun the preparations to deploy Tornado and Typhoon warplanes along with

aerial refuelling and surveillance aircraft. He said the planes would move “in

the coming hours” to bases where they could start implementing the no-fly zone.

“This is about protecting the Libyan people and saving

lives,” the prime minister said. “The world has watched Qaddafi brutally

crushing his own people. We expect brutal attacks. Qaddafi is preparing for a

violent assault on Benghazi.”

lives,” the prime minister said. “The world has watched Qaddafi brutally

crushing his own people. We expect brutal attacks. Qaddafi is preparing for a

violent assault on Benghazi.”

“Any decision to put the men and women of our armed forces

into harm’s way should only be taken when absolutely necessary,” he said. “But

I believe that we cannot stand back and let a dictator whose people have

rejected him kill his people indiscriminately. To do so would send a chilling

signal to others.”

into harm’s way should only be taken when absolutely necessary,” he said. “But

I believe that we cannot stand back and let a dictator whose people have

rejected him kill his people indiscriminately. To do so would send a chilling

signal to others.”

“The clock is now ticking,” Mr Cameron said. “We need a

sense of urgency because we don’t want to see a bloodbath in Benghazi.”

Responding to criticism from parliamentarians about getting Britain involved

militarily, Mr Cameron retorted: “To pass a resolution like this and then just

stand back and hope someone in the region would enforce it is wrong.”

sense of urgency because we don’t want to see a bloodbath in Benghazi.”

Responding to criticism from parliamentarians about getting Britain involved

militarily, Mr Cameron retorted: “To pass a resolution like this and then just

stand back and hope someone in the region would enforce it is wrong.”

Mr Cameron indicated that a statement would be issued before

Saturday’s meeting in Paris, “to tell Qaddafi what is expected.”

Saturday’s meeting in Paris, “to tell Qaddafi what is expected.”

Before the ceasefire was announced, the Libyan leader had

already signalled his intentions in Benghazi.

already signalled his intentions in Benghazi.

“We will come house by house, room by room. It’s over. The

issue has been decided,” Colonel Qaddafi said Thursday on a radio call-in show

before the United Nations vote. To those who continued to resist, he vowed: “We

will find you in your closets. We will have no mercy and no pity.”

issue has been decided,” Colonel Qaddafi said Thursday on a radio call-in show

before the United Nations vote. To those who continued to resist, he vowed: “We

will find you in your closets. We will have no mercy and no pity.”

In a television broadcast later, he added: “The world is

crazy, and we will be crazy, too.”

crazy, and we will be crazy, too.”

Amr Moussa, the secretary general of the Arab League, which

had supported the no-fly proposal, told Reuters on Friday: “‘the goal is to

protect civilians first of all, and not to invade or occupy.”

had supported the no-fly proposal, told Reuters on Friday: “‘the goal is to

protect civilians first of all, and not to invade or occupy.”

Before Mr Koussa’s announcement, forces loyal to Colonel

Qaddafi unleashed a barrage of fire against Misurata in the west, news reports

said, while his son Seif al-Islam was quoted as saying government forces would

encircle Benghazi in the east. Eurocontrol, Europe’s air traffic control

agency, said in Brussels on Friday that Libya had closed its airspace. It was

not immediately clear whether loyalist troops had begun honouring the

cease-fire.

Qaddafi unleashed a barrage of fire against Misurata in the west, news reports

said, while his son Seif al-Islam was quoted as saying government forces would

encircle Benghazi in the east. Eurocontrol, Europe’s air traffic control

agency, said in Brussels on Friday that Libya had closed its airspace. It was

not immediately clear whether loyalist troops had begun honouring the

cease-fire.

The Security Council vote seemed to have divided Europeans,

with Germany saying it would not participate while Norway was reported as

saying it would. In the region, Turkey was reported to have registered

opposition, but Qatar said it would support the operation. In Tripoli,

government minders told journalists on Friday that they could not leave their

hotel for their own safety, saying that in the aftermath of the United Nations

vote, residents might attack or even shoot foreigners. The extent of the danger

was unclear.

with Germany saying it would not participate while Norway was reported as

saying it would. In the region, Turkey was reported to have registered

opposition, but Qatar said it would support the operation. In Tripoli,

government minders told journalists on Friday that they could not leave their

hotel for their own safety, saying that in the aftermath of the United Nations

vote, residents might attack or even shoot foreigners. The extent of the danger

was unclear.

On Thursday night in New York, after days of often

acrimonious debate played out against a desperate clock, and with Colonel

Qaddafi’s troops within 100 miles of Benghazi, the Security Council authorized

member nations to take “all necessary measures” to protect civilians,

diplomatic code words calling for military action.

acrimonious debate played out against a desperate clock, and with Colonel

Qaddafi’s troops within 100 miles of Benghazi, the Security Council authorized

member nations to take “all necessary measures” to protect civilians,

diplomatic code words calling for military action.

Diplomats said the resolution — which passed with 10 votes,

including the United States, and abstentions from Russia, China, Germany,

Brazil and India — was written in sweeping terms to allow for a wide range of

actions, including strikes on air-defenses systems and missile attacks from

ships.

including the United States, and abstentions from Russia, China, Germany,

Brazil and India — was written in sweeping terms to allow for a wide range of

actions, including strikes on air-defenses systems and missile attacks from

ships.

Benghazi erupted in celebration at news of the resolution’s

passage. “We are embracing each other,” said Imam Bugaighis, spokeswoman for

the rebel council in Benghazi. “The people are euphoric. Although a bit late,

the international society did not let us down.”

passage. “We are embracing each other,” said Imam Bugaighis, spokeswoman for

the rebel council in Benghazi. “The people are euphoric. Although a bit late,

the international society did not let us down.”

The vote, which came after rising calls for help from the

Arab world and anguished debate in Washington, left unanswered many critical

questions about who would take charge, what role the United States would play

and whether there was still enough time to stop Colonel Qaddafi from

recapturing Benghazi and crushing a rebellion that had once seemed likely to

drive him from power. After the vote, President Obama met with the National

Security Council to discuss the possible options, European officials said. He

also spoke by telephone on Thursday evening with Mr Cameron and Mr Sarkozy, the

White House said.

Arab world and anguished debate in Washington, left unanswered many critical

questions about who would take charge, what role the United States would play

and whether there was still enough time to stop Colonel Qaddafi from

recapturing Benghazi and crushing a rebellion that had once seemed likely to

drive him from power. After the vote, President Obama met with the National

Security Council to discuss the possible options, European officials said. He

also spoke by telephone on Thursday evening with Mr Cameron and Mr Sarkozy, the

White House said.

A Pentagon official said Thursday that decisions were still

being made about what kind of military action, if any, the United States might

take with the allies against Libya. The official said that contingency planning

continued across a full range of operations, including a no-fly zone, but that

it was unclear how much the United States would become involved beyond

providing support.

being made about what kind of military action, if any, the United States might

take with the allies against Libya. The official said that contingency planning

continued across a full range of operations, including a no-fly zone, but that

it was unclear how much the United States would become involved beyond

providing support.

That support is likely to consist of much of what the United

States already has in the region — Awakes radar planes to help with air traffic

control should there be airstrikes, other surveillance aircraft and about 400

Marines aboard two amphibious assault ships in the region, the Kearsarge and

the Ponce.

States already has in the region — Awakes radar planes to help with air traffic

control should there be airstrikes, other surveillance aircraft and about 400

Marines aboard two amphibious assault ships in the region, the Kearsarge and

the Ponce.

The Americans could also provide signal-jamming aircraft in

international airspace to muddle Libyan government communications with its

military units.

international airspace to muddle Libyan government communications with its

military units.

The United States has played a complicated role in the

debate over military involvement, initially expressing great reluctance about

being drawn into another armed conflict in a Muslim country but subsequently

unnerved by the reports of Colonel Qaddafi’s gains.

debate over military involvement, initially expressing great reluctance about

being drawn into another armed conflict in a Muslim country but subsequently

unnerved by the reports of Colonel Qaddafi’s gains.

But diplomats said the moral imperative of protecting

civilians from Colonel Qaddafi and the political imperative of United States

not watching from the side-lines while a notorious dictator violently crushed a

democratic rebellion had helped wipe away lingering doubts.

civilians from Colonel Qaddafi and the political imperative of United States

not watching from the side-lines while a notorious dictator violently crushed a

democratic rebellion had helped wipe away lingering doubts.

Characterizing Colonel Qaddafi as a menacing “creature”

lacking a moral compass, Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton said

Thursday that the international community had little choice but to act. “There

is no good choice here. If you don’t get him out and if you don’t support the

opposition and he stays in power, there’s no telling what he will do,” Mrs.

Clinton said from Tunisia on Thursday.

lacking a moral compass, Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton said

Thursday that the international community had little choice but to act. “There

is no good choice here. If you don’t get him out and if you don’t support the

opposition and he stays in power, there’s no telling what he will do,” Mrs.

Clinton said from Tunisia on Thursday.

The Security Council resolution — sponsored by Lebanon,

another Arab state, and strongly backed by France, Britain and the United

States — explicitly mentions the need to protect civilians in the rebel

stronghold Benghazi, “while excluding an occupation force.” It calls to

“establish a ban on all flights in the airspace” and an immediate cease-fire.

another Arab state, and strongly backed by France, Britain and the United

States — explicitly mentions the need to protect civilians in the rebel

stronghold Benghazi, “while excluding an occupation force.” It calls to

“establish a ban on all flights in the airspace” and an immediate cease-fire.

Mrs. Clinton said Thursday that establishing a no-fly zone

over Libya would require bombing targets inside the country to protect planes

and pilots. She said other options being considered included the use of drones

and arming rebel forces, though not ground troops, an option that appeared to

be ruled out Thursday by the State Department’s highest-ranking career

diplomat, Under Secretary William J. Burns.

over Libya would require bombing targets inside the country to protect planes

and pilots. She said other options being considered included the use of drones

and arming rebel forces, though not ground troops, an option that appeared to

be ruled out Thursday by the State Department’s highest-ranking career

diplomat, Under Secretary William J. Burns.

The vote was also a seminal moment for the 192-member United

Nations and was being watched closely as a critical test of its ability to take

collective action to prevent atrocities against civilians. Diplomats said the spectre

of former conflicts in Bosnia, Rwanda and Darfur, when a divided and sluggish

Security Council was seen to have cost lives, had given a sense of moral

urgency to Thursday’s debate. Yet some critics also noted that a no-fly zone

authorized in the early 1990s in Bosnia had failed to prevent some of the worst

massacres there, including the Srebrenica massacre.

Nations and was being watched closely as a critical test of its ability to take

collective action to prevent atrocities against civilians. Diplomats said the spectre

of former conflicts in Bosnia, Rwanda and Darfur, when a divided and sluggish

Security Council was seen to have cost lives, had given a sense of moral

urgency to Thursday’s debate. Yet some critics also noted that a no-fly zone

authorized in the early 1990s in Bosnia had failed to prevent some of the worst

massacres there, including the Srebrenica massacre.

No comments:

Post a Comment